- READ MORE: Bill Gates-backed plan to block the sun and reverse global warming

It might sound like a Bond villain's sinister plot, but dimming the sun could be the key to fighting climate change .

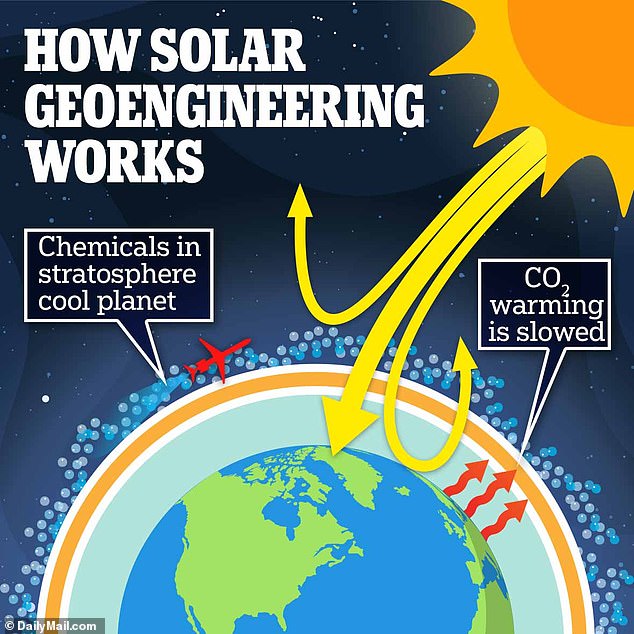

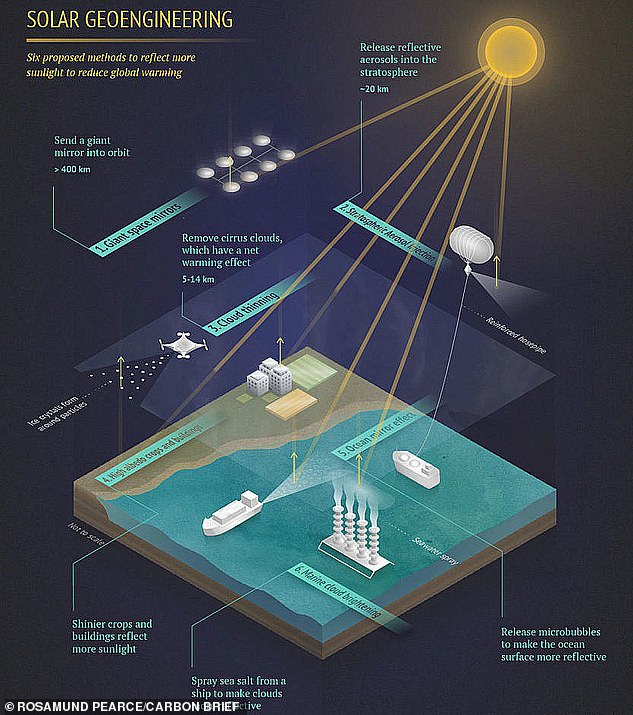

Scientists believe a controversial geoengineering technique called stratospheric aerosol injection could be used to cool Earth.

Similar to sunscreen for Earth, this method involves dispersing small reflective particles into the atmosphere to reduce the amount of sunlight reaching Earth .

Now, researchers from the University College London (UCL) claim this can be done with existing commercial aircraft.

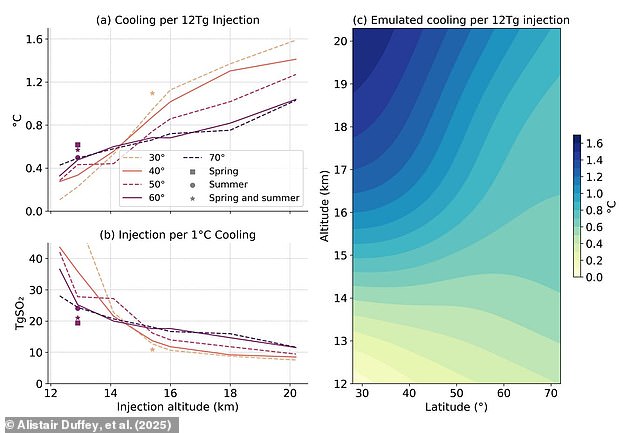

Earlier, researchers believed that aerosol injection would only have a cooling effect on the climate if the particles were released at heights exceeding 12 miles (20 kilometers).

However, new computational simulations indicate that introducing particles at an altitude of merely eight miles (13 kilometers) above the poles could lead to a significant reduction in global temperatures.

This height has been attained by certain commercial planes such as the Boeing 777F, which suggests that geoengineering could begin much earlier than anticipated.

Alistair Duffey, a PhD candidate from University College London who leads the study, informed MailOnline: "We cannot conclude if stratospheric aerosol injection is truly beneficial; our knowledge remains insufficient for policymakers to reach an educated choice. This underscores the necessity of further investigation in this field."

As the planet receives warmth from the sun, the heat slowly disperses back into space, ensuring that Earth maintains a relatively stable temperature.

However, when greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide are emitted through the combustion of fossil fuels, they function akin to an insulating layer around Earth, hindering the escape of heat.

Research spanning decades has unequivocally demonstrated that the Earth is heating up as a result of accumulating greenhouse gases.

The concept underlying geoengineering methods such as stratospheric aerosol injection is to mitigate that warmth, by decreasing the quantity of heat that reaches Earth initially .

For this research, the scientists employed a computer model of the climate to examine the outcomes of injecting sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.

Sulfur dioxide is a damaging gas typically released when fossil fuels are burned. It can pose risks to human health at elevated levels and contributes to making rainfall more acidic.

However, when it mixes with other molecules in the air it forms an aerosol, a suspension of fine droplets, which are highly reflective.

These shiny droplets reflect the radiation from the sun back out into space before it has a chance to warm the planet, balancing out some of the warming produced by greenhouse gases.

The researchers' simulations found that injecting 12 million tonnes of sulphur dioxide a year at altitudes of eight miles (13km) during spring and summer could cool the climate by 0.6°C (1.08°F).

That is roughly the same amount of sulphur dioxide released by the eruption of the Mount Pinatubo volcano in 1991, which also produced an observable dip in global temperatures .

These lower-altitude injections weren't as effective as injections above 13 miles since the aerosol particles last just months rather than several years before falling to Earth.

Similarly, the simulation indicated that low-altitude injections resulted in a significant cooling impact only when conducted at latitudes 60 degrees north and south of the equator.

This corresponds approximately to the latitude of Oslo, Norway, or Anchorage, Alaska, in the northern region and lies beneath the southernmost point of South America in the southern area.

However, this research provides the initial proof that geoengineering can be executed using technologies we have access to at present.

Co-author Wake Smith from Yale University states, "Even though existing planes would need significant modifications to serve as operational tankers, this approach would be considerably faster compared to developing a new high-altitude aircraft."

Nevertheless, the researchers caution that stratospheric injection is not a 'panacea' for climate change – and this method comes with possible risks.

Mr Duffey states: " numerous hazards exist, covering everything from immediate physical consequences like acid rain to more nuanced issues concerning management, disputes, and global political strain."

Moreover, even though low-altitude injections are easier to implement, they might lead to greater issues as they necessitate larger amounts of sulfur to produce equivalent global cooling effects.

One of the major critiques of geoengineering is that it diverts attention away from implementing the genuine, challenging alterations required to curb climate change.

'Major concern lies in the potential distraction caused by earnestly debating these concepts, which could divert attention away from the crucial mission of achieving net-zero emissions,' Mr Duffey notes.

'Evidence suggests it could aid in mitigating the effects of climate change, though this would require being coupled with swift and substantial reductions in emissions.'

The study’s co-author, Dr Matthew Henry from the University of Exeter, states: "Injecting aerosols into the stratosphere is definitely not an alternative to reducing greenhouse gases. Any possible adverse consequences intensify along with increased cooling efforts; achieving lasting climate stability requires reaching net-zero emissions."

Read more